Business environments in which Web services (WS) must function are seldom static. Key characteristics of service providers such as the reliability rate of their services and other quality-of-service parameters, which may affect WS compositions tend to be volatile. As a concrete example, consider a supply chain in which two suppliers compete for orders from a large manufacturer. The sequence in which the manufacturer uses the services of the two suppliers depends on the probability with which the suppliers usually satisfy the orders and the cost of using them. If the preferred supplier's rate of order satisfaction drops suddenly (due to unforeseen circumstances), a cost-conscious manufacturer should replace it with the other supplier to remain optimal.

The key components for maintaining an adaptive Web process - a

business process with WSs as its components - are then:

![]() up-to-date knowledge of the

current parameters of the service providers, and

up-to-date knowledge of the

current parameters of the service providers, and ![]() a measure of the suboptimality of the current

Web process. Both these aspects come with their own attendant

challenges spanning from how to obtain the new service parameters

and from which providers to finding approaches that associate a

measure of optimality to the Web process. In addition, if there

is a cost to obtaining the new information, not all changes to

the Web process composition effected by the revised information

may be worth the cost.

a measure of the suboptimality of the current

Web process. Both these aspects come with their own attendant

challenges spanning from how to obtain the new service parameters

and from which providers to finding approaches that associate a

measure of optimality to the Web process. In addition, if there

is a cost to obtaining the new information, not all changes to

the Web process composition effected by the revised information

may be worth the cost.

Prevalent approaches to automatically composing Web processes use methods within classical planning [13] and decision-theoretic planning [4]. These rely on pre-specified models of the process environment to generate the WS compositions. In [5], Harney and Doshi introduced a mechanism called the value of changed information (VOC) by which the expected impact of the revised information on the Web process could be calculated. The approach involved selectively querying the service providers for their revised parameters. If the change brought about by the revised information was worth the cost of obtaining it, the Web process was reformulated.1 Thus, the VOC mechanism avoids ``unnecessary'' queries in comparison to the naive approach of, say, periodically querying all the service providers. While this approach results in adaptive Web processes that incur lesser costs in simulated volatile environments [5], computationally the approach turns out to be inefficient.

In this paper, we improve on the previous VOC based approach

to adaptation by using the insight that service providers are

often able to guarantee that the parameters of their services

will persist for some amount of time. Thus, we need not consider

querying those service providers for revised information whose

previously obtained information has not expired. We incorporate

this insight into the VOC formulation, and call the new approach,

the value of changed information with expiraton times

(VOC

![]() ). Because VOC

). Because VOC

![]() focuses the

computations on only those services whose parameters could have

changed, it is computationally more efficient than the

traditional VOC, while resulting in Web processes that are as

cost-efficient in volatile environments as those in the previous

approach.

focuses the

computations on only those services whose parameters could have

changed, it is computationally more efficient than the

traditional VOC, while resulting in Web processes that are as

cost-efficient in volatile environments as those in the previous

approach.

We theoretically show that the adaptation of the Web processes

using VOC

![]() is as good as the

one using VOC and empirically demonstrate that, on average, the

approach based on VOC

is as good as the

one using VOC and empirically demonstrate that, on average, the

approach based on VOC

![]() is computationally

less intensive. In the worst case, the two approaches exhibit

identical asymptotic complexities. For the purpose of empirical

evaluation, we utilize two realistic Web process scenarios - a

supply chain and a clinical administrative pathway. Within our

service-oriented architecture (SOA), we represent the

manufacturer's and hospital's Web processes using WS-BPEL

[6], and the provider services as

well as a service for computing the VOC

is computationally

less intensive. In the worst case, the two approaches exhibit

identical asymptotic complexities. For the purpose of empirical

evaluation, we utilize two realistic Web process scenarios - a

supply chain and a clinical administrative pathway. Within our

service-oriented architecture (SOA), we represent the

manufacturer's and hospital's Web processes using WS-BPEL

[6], and the provider services as

well as a service for computing the VOC

![]() using WSDL

[12].

using WSDL

[12].

Recently, researchers are increasingly turning their attention to managing processes in volatile environments. Au et al. [2] obtain current parameters about the Web process by querying Web service providers when the parameters expire. While this is similar in concept to our approach, plan recomputation is assumed to take place irrespective of whether the revised parameter values are expected to bring about a change in the composition. This may lead to frequent unnecessary computations. In [3], several alternate plans are pre-specified at the logical level, physical level, and the runtime level. Depending on the type of changes in the environment, alternative plans from these three stages are selected. While capable of adapting to several different events, many of the alternative pre-specified plans may not be used making the approach inefficient, and there is no guarantee of optimality of the resulting Web processes. In a somewhat different vein, Verma et al. [11] explore adaptation in Web processes in the presence of coordination constraints between different WSs. We do not consider such constraints here.

In [10], graph based techniques were used to evaluate the feasibility and correctness of changes at the process instance level. Muller et al. [8] propose a workflow adaptation strategy based on pre-defined event-condition-action rules that are triggered when a change in the evironment occurs. While the rules provide a good basis for performing contingency actions, they are limited in the fact that they cannot account for all possible actions and scenarios that may arise in complex workflows. Additionally, the above work does not address long term optimality of process adaptation. Doshi et al. [4] offers such a solution using a technique that manages the dynamism of Web process environments through Bayesian learning. The process model parameters are updated based on previous interactions with the individual Web services and the composition plan is regenerated using these updates. This method suffers from being slow in updating the parameters, and the approach may result in plan recomputations that do not bring about any change in the Web process.

Several characteristics of the service providers who participate in a Web process may change during the life-cycle of a process. For example, in a supply chain, the cost of using the preferred supplier's services may increase, and/or the probability with which the preferred supplier meets the orders may reduce. Not all updates of the parameters cause changes in the process composition. Furthermore, the change effected by the revised information may not be worth the cost of obtaining it. In light of these arguments, the VOC-based approach [5] provides a method that will suggest a query, only when the queried information is expected to be sufficiently valuable to obtain.

While the approach is applicable to any model based process

composition technique, for the purpose of illustration, a

decision-theoretic planning technique is utilized for composing

Web processes [4].

Decision-theoretic planners such as MDPs [9] model the process environment,

![]() , using a sextuplet:

, using a sextuplet:

The VOC formulation adopts a myopic approach to information revision, in which a single provider is queried at a time for new information. For example, this would translate to asking, say, only the preferred supplier for its current rates of order satisfaction, as opposed to both the preferred supplier and the other supplier, simultaneously. The revised information may change the probability with which the preferred supplier is known to satisfy the order, contained in the transition function.

Let

![]() denote the

expected cost of following the optimal policy,

denote the

expected cost of following the optimal policy, ![]() , from the state

, from the state ![]() when the revised transition function,

when the revised transition function, ![]() is used. Since the actual revised transition probability is not

known unless we query the service provider, computing the VOC

involves averaging over all possible values of the revised

transition probability, using the current belief distributions

over their values. These distributions may be provided by the

service providers through pre-defined service-level agreements or

they could be learned from previous interactions with the service

providers. Let

is used. Since the actual revised transition probability is not

known unless we query the service provider, computing the VOC

involves averaging over all possible values of the revised

transition probability, using the current belief distributions

over their values. These distributions may be provided by the

service providers through pre-defined service-level agreements or

they could be learned from previous interactions with the service

providers. Let

![]() be the

expected cost of following the original policy,

be the

expected cost of following the original policy, ![]() from the state

from the state ![]() in the

context of the revised model parameter,

in the

context of the revised model parameter, ![]() . Note that the policy,

. Note that the policy, ![]() , is optimal in the absence of any revised

information. The expected value of change due to the revised

transition probabilities is formulated as:

, is optimal in the absence of any revised

information. The expected value of change due to the revised

transition probabilities is formulated as:

The probability ![]() represents

a revised probability of transition on performing a particular

action, and

represents

a revised probability of transition on performing a particular

action, and

![]() represents the belief over the transition probabilities. Notice

that in order to calculate the VOC, we must compute the revised

values,

represents the belief over the transition probabilities. Notice

that in order to calculate the VOC, we must compute the revised

values,

![]() and

and

![]() , for all

possible

, for all

possible ![]() and average over

their difference based on our distribution over

and average over

their difference based on our distribution over ![]() . Computing

. Computing

![]() , which

represents the expected cost of following the policy

, which

represents the expected cost of following the policy ![]() from state

from state ![]() is straightforward since it does not involve the

optimization operation over all actions. However, the revised

value function

is straightforward since it does not involve the

optimization operation over all actions. However, the revised

value function

![]() is computed

by solving the MDP which may become computationally expensive

with large problems.

is computed

by solving the MDP which may become computationally expensive

with large problems.

Analogous to the value of perfect information, VOC is guaranteed to be non-negative at each state of the Web process. For the proof see [5].

Since querying the model parameters and obtaining the revised information may be expensive, we must undertake the querying only if we expect it to pay off. In other words, we query for new information from a state of the Web process only if the VOC due to the revised information in that state is greater than the query cost. More formally, we query if:

In order to formulate and execute the Web process, we simply look up the current state of the Web process in the policy and execute the WS prescribed by the policy for that state. The response of the WS invocation determines the next state of the Web process. The composition of the Web process is adapted to fluctuations in the model parameters by interleaving the formulation with VOC computations. The algorithm for the adaptive Web process composition is shown in Fig. 1.

|

For each state encountered during the execution of the Web

process, a service provider is queried for new information if the

query is expected to bring about a change in the Web process that

exceeds the query cost. For example, in the supply chain process,

we select and query a supplier for its current rate of order

satisfactions. Of all the suppliers, we select the one whose

possible new rate of order satisfaction is expected to bring

about the most change in the Web process, and this change exceeds

the cost of querying that provider. In other words, we select the

service provider associated with the WS invocation, ![]() , to possibly query for whom

the VOC is maximum:

, to possibly query for whom

the VOC is maximum:

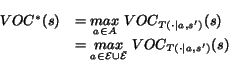

Calculating the VOC![]() as shown in Eq.

2 is computationally

intensive. It involves iterating over all the service providers

and computing the VOC for each. Because there could be many

service providers participating in the Web process, a more

selective approach is needed to obtain computational efficiency.

We present one such method next.

as shown in Eq.

2 is computationally

intensive. It involves iterating over all the service providers

and computing the VOC for each. Because there could be many

service providers participating in the Web process, a more

selective approach is needed to obtain computational efficiency.

We present one such method next.

In order to illustrate our approach we present two example scenarios:

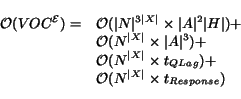

MS XBox 360 Supply Chain Our first scenario is a simplified version of the supply chain employed by Microsoft (MS) for the production of its XBox 360 gaming console [7]. MS engages a variety of suppliers and contract manufacturers to deliver the components that are crucial to the production of the gaming console. Because MS outsources key manufacturing operations, it needs to retain tight control over those external processes to ensure that the suppliers and contract manufacturers meet service level agreements.

![\includegraphics[width=3.5in]{Figs/MSXBOX.eps}](VOC_Exp-img50.png)

|

In Fig. 2, we focus on a simplified supply chain scenario in which MS chooses a contracted console manufacturer, resonsible for assembling the console, and a contracted graphics processing unit (GPU) manufacturer who is responsible for building the advanced GPU chips. We assume that the invocations will be carried out in a sequential manner, beginning with the GPU followed by the console. 2 We assume that each of the manufacturers has the option to order their components from three different suppliers. They may order from a preferred supplier with which they usually interact. The manufacturers may also order the parts from other suppliers or resort to the spot market. A costing analysis reveals that the least cost will be incurred if the order is satisfied by the preferred supplier. They will incur increasing costs as they try to fulfill the orders by procuring the console and GPU chips from another supplier and the spot market.

Clearly, MS and its manufacturers must choose from several candidate processes. For example, they may initially attempt to satisfy the order of GPU chips from the preferred supplier. If the preferred supplier is unable to satisfy the order, MS may resort to ordering parts from some other supplier. Another potential process may involve bypassing the preferred supplier, since MS strongly believes that the preferred supplier will not satisfy the order. It may then initiate a status check on some other supplier. These example processes reveal two important factors for selecting the optimal one. First, MS must accurately know the certainty with which the console and GPU chip orders will be satisfied by each of its supplier choices. Second, at each stage, rather than greedily selecting an action with the least cost, MS must select the action which is expected to be optimal over the long term.

Patient Transfer A hospital receives a patient who has complained of a particular ailment. The patient is first checked into the hospital and then seen by one of the hospital's physicians. He may, upon examination, decide to transfer the patient to a secondary care provider for specialist treatment. For this example, we assume that the hospital has a choice of four secondary care givers to select from with differing vacancy rates and costs of treatment, with the preferred one having the best vacancy rate and least cost (see Fig. 3).

Similar to our previous example, several candidate Web processes present themselves. For example, the physician may decide not to transfer the patient, instead opting for in-house treatment. However, if the physician concludes that specialist treatment is required, several factors weigh in toward selecting the secondary care giver. These include, the typical vacancy rates of the care givers, costs of treatment, and geographic proximity.

![\includegraphics[width=3.5in]{Figs/PTTrans.eps}](VOC_Exp-img51.png)

|

The process flows in both the supply chain and the patient transfer scenarios hinge on the rates of order satisfaction and vacancy rates, respectively. If the order satisfaction rate of the preferred supplier or the vacancy rate of the preferred secondary caregiver drops, the processes need to be adapted to remain cost-effective.

As we mentioned previously, in order to select a service provider for querying for revised information, the previous approach [5] required iterating over all the WSs and selecting the one which results in the largest VOC. For large Web processes, there could be several participating WSs, making the process of selection computationally intensive.

To address this challenge, we use the insight that service

providers are often able to guarantee that their reliability

rates and other quality-of-service parameters will remain fixed

for some time, ![]() , after which they

may vary. WS providers may define

, after which they

may vary. WS providers may define ![]() in a WS-Agreement document [1] as we show later.

in a WS-Agreement document [1] as we show later.

Given a way to keep track of guarantees of which WSs have expired, we may compute the VOC for only those service providers whose guarantees have expired and select among them. This is because a possible query to the others will return back parameter values that are unchanged from those used in formulating the current Web process. Thus such queries will cause no adaptation in the Web process, and may be safely ignored.

In a departure from [5], we assume that, in

addition to providing their current reliability rates, the

service providers also give the duration of time for which the

current reliability rates are guaranteed to remain unchanged. We

call this duration as the expiration time of the revised

information. Let ![]() represent the

action of invoking the WS,

represent the

action of invoking the WS, ![]() ,

,

![]() be the current set of

actions representing the invocations of WSs whose guarantees have

expired, then we define the maximum VOC, VOC

be the current set of

actions representing the invocations of WSs whose guarantees have

expired, then we define the maximum VOC, VOC

![]() , as:

, as:

The challenge then is to correctly maintain the set,

![]() , during the lifetime

of the Web process; we show one such way of doing this next.

, during the lifetime

of the Web process; we show one such way of doing this next.

In Fig. 4, we

show the algorithm for generating, executing, and adapting the

Web process to a volatile environment using VOC

![]() . The algorithm

takes as input the initial state of the process, and a policy,

. The algorithm

takes as input the initial state of the process, and a policy,

![]() , obtained by solving the

process model (Section 3), which prescribes which WS

to invoke from each state of the process.

, obtained by solving the

process model (Section 3), which prescribes which WS

to invoke from each state of the process.

As we mentioned before, we associate with each WS![]() participating in the process,

an expiration time,

participating in the process,

an expiration time,

![]() , during

which the parameters of the WS such as its reliability are

guaranteed to be fixed. We begin by checking which of the WSs

have expired guarantees (lines 5-10) and updating the set,

, during

which the parameters of the WS such as its reliability are

guaranteed to be fixed. We begin by checking which of the WSs

have expired guarantees (lines 5-10) and updating the set,

![]() , with those that have

expired. The next step is to compute VOC

, with those that have

expired. The next step is to compute VOC

![]() (Eq. 3), which will suggest a service

provider among the expired set,

(Eq. 3), which will suggest a service

provider among the expired set,

![]() , to query for revised

information that is expected to bring about most change in the

Web process.

, to query for revised

information that is expected to bring about most change in the

Web process.

Notice that a WS might expire while computing VOC

![]() . We must anticipate

this and add those services in advance to the set,

. We must anticipate

this and add those services in advance to the set,

![]() , so that they are

taken under consideration while computing VOC

, so that they are

taken under consideration while computing VOC

![]() . In line 8, the

algorithm invokes the procedure in Fig. 5, which finds out which WSs among

the unexpired ones (denoted by

. In line 8, the

algorithm invokes the procedure in Fig. 5, which finds out which WSs among

the unexpired ones (denoted by

![]() ) may expire

while computing VOC

) may expire

while computing VOC

![]() and adds these to

the set

and adds these to

the set

![]() . We note that if a WS

is added to

. We note that if a WS

is added to

![]() , the time taken to

compute VOC

, the time taken to

compute VOC

![]() may increase,

during which other WSs may expire. We consider this by

recursively invoking the procedure until no more WSs are added to

the set,

may increase,

during which other WSs may expire. We consider this by

recursively invoking the procedure until no more WSs are added to

the set,

![]() . The time taken to

compute VOC

. The time taken to

compute VOC

![]() ,

,

![]() , needs to

be anticipated; if

, needs to

be anticipated; if

![]() is the time taken to

compute the VOC (Eq. 1), then

is the time taken to

compute the VOC (Eq. 1), then

![]() .

Notice that

.

Notice that

![]() is fixed and may be

obtained a'priori.

is fixed and may be

obtained a'priori.

If VOC

![]() exceeds the cost of

querying the service provider, then we query the provider for the

new reliability rates, which form the new

exceeds the cost of

querying the service provider, then we query the provider for the

new reliability rates, which form the new ![]() in the process model. We also add the time taken to

perform the VOC

in the process model. We also add the time taken to

perform the VOC

![]() calculations to the

cumulative time counter associated with each WS (lines 11-15). On

querying, in addition to obtaining the possibly revised

information, we also obtain the new expiration times for the

information. Thus, the counter for the WS that is queried is

reset.

calculations to the

cumulative time counter associated with each WS (lines 11-15). On

querying, in addition to obtaining the possibly revised

information, we also obtain the new expiration times for the

information. Thus, the counter for the WS that is queried is

reset.

We observe that querying for information is not a constant

time step operation, but must take into account the time taken

for the request to reach the provider, the provider's

information-providing WS to complete its computations, and for

the the response to arrive back at the process. We denote the

total time consumed in querying as ![]() , which is depicted in Fig. 6.

, which is depicted in Fig. 6.

The revised information is integrated into the process model

and a new policy is recomputed to maintain optimality of the Web

process. However, recomputation of the policy is not always

necessary, and runtime changes could be made to the process.

Here, the time counters must be updated again to account for the

time taken to recalculate the policy. Finally, the queried WS is

removed from

![]() (lines 21-26). We

observe that the times,

(lines 21-26). We

observe that the times, ![]() and

and ![]() could be calculated in

real-time (online) using timestamps before and after the

calcuations.

could be calculated in

real-time (online) using timestamps before and after the

calcuations.

Of course, if the query cost exceeds

![]() , then we ignore

the previously mentioned steps, and simply invoke the WS that the

original policy recommends. Obtaining a response from the invoked

WS may not be a constant time operation but may depend on

external factors, as shown in Fig. 7. Let

, then we ignore

the previously mentioned steps, and simply invoke the WS that the

original policy recommends. Obtaining a response from the invoked

WS may not be a constant time operation but may depend on

external factors, as shown in Fig. 7. Let

![]() be the time elapsed,

then this time is added to all the cumulative time counters

(lines 28-33).

be the time elapsed,

then this time is added to all the cumulative time counters

(lines 28-33).

We first show that given an identical input, adaptation using

VOC

![]() results in the same

set of Web processes as compared to adaptation using

VOC

results in the same

set of Web processes as compared to adaptation using

VOC![]() [5].

[5].

We consider two cases: ![]() If

the WS with the maximum VOC selected for querying has expired,

If

the WS with the maximum VOC selected for querying has expired,

![]() , then

VOC

, then

VOC![]() = VOC

= VOC

![]() for every state,

and the Web process will be adapted identically to when VOC

for every state,

and the Web process will be adapted identically to when VOC

![]() is used. On the

other hand,

is used. On the

other hand, ![]() if the WS

associated with the maximum VOC has not expired, then since the

revised information is guaranteed to be unchanged,

VOC

if the WS

associated with the maximum VOC has not expired, then since the

revised information is guaranteed to be unchanged,

VOC![]() = 0, and the Web process also

remains unchanged. Thus, for both the cases, the resulting Web

process will be identical to the one generated when VOC

= 0, and the Web process also

remains unchanged. Thus, for both the cases, the resulting Web

process will be identical to the one generated when VOC

![]() is used.

is used.

![]()

We derive the worst case complexity of the adaptation next.

While the worst case complexity is similar to the complexity of

adaptation using VOC![]() , on average we

expect significant computational gains from considering

expiration times. We demonstrate these gains experimentally in

the next section. A theoretical analysis of the average case

complexity of this approach is part of our future work.

, on average we

expect significant computational gains from considering

expiration times. We demonstrate these gains experimentally in

the next section. A theoretical analysis of the average case

complexity of this approach is part of our future work.

Within the body of the loop we focus on three operations in

particular. First, lines 5-10 update the set of expired

services,

![]() . Here, a loop

iterates over all WSs (ie,

. Here, a loop

iterates over all WSs (ie,![]() ) effectively having an execution time in

the order of

) effectively having an execution time in

the order of

![]() .

However, each pass of the loop calls the AddExpiredServices

procedure (Fig 5), which

terminates when no more services are added to

.

However, each pass of the loop calls the AddExpiredServices

procedure (Fig 5), which

terminates when no more services are added to

![]() . In the worst case,

this procedure will add one service to

. In the worst case,

this procedure will add one service to

![]() , and then

, and then

![]() will

increase such that one more service will expire, in which case

another service will be added to

will

increase such that one more service will expire, in which case

another service will be added to

![]() ; this process is

repeated until all the services are added. We may then write

the following recurrence for the runtime of this procedure:

; this process is

repeated until all the services are added. We may then write

the following recurrence for the runtime of this procedure:

Thus the total runtime complexity is:

We first outline our SOA in which we wrap the VOC

![]() computations in

WSDL based internal Web services, followed by our experimental

results on the performance of the adaptive Web process as

compared to the previous approach.

computations in

WSDL based internal Web services, followed by our experimental

results on the performance of the adaptive Web process as

compared to the previous approach.

The algorithm described in Fig. 4 is implemented as a

WS-BPEL [6] flow while all WSs

were implemented using WSDL [12].

To the WS-BPEL flow, we give the optimal policy, ![]() , and the start state as input. Our experiments

utilized IBM's BPWS4J engine for executing the BPEL process and

AXIS 2.0 as the container for the WSs. We show our SOA in Fig.

8.

, and the start state as input. Our experiments

utilized IBM's BPWS4J engine for executing the BPEL process and

AXIS 2.0 as the container for the WSs. We show our SOA in Fig.

8.

Within our SOA, we provide internal WSs for solving the MDP

model of the Web process and generating the policy, and computing

the VOC

![]() . If the VOC

. If the VOC

![]() exceeds the cost

of querying a particular service provider (this cost is also

provided as an input), the WS-BPEL flow invokes a special WS

whose function is to query the service provider's

information-providing WSs for revised information and the new

expiration times. This information is used to formulate and solve

a new MDP and the output policy is fed back to the WS-BPEL flow.

This policy is used by the WS-BPEL flow to invoke the prescribed

external WS and the response is used to formulate the next state

of the process. This procedure continues until the goal state is

reached.

exceeds the cost

of querying a particular service provider (this cost is also

provided as an input), the WS-BPEL flow invokes a special WS

whose function is to query the service provider's

information-providing WSs for revised information and the new

expiration times. This information is used to formulate and solve

a new MDP and the output policy is fed back to the WS-BPEL flow.

This policy is used by the WS-BPEL flow to invoke the prescribed

external WS and the response is used to formulate the next state

of the process. This procedure continues until the goal state is

reached.

The objective of our experimental evaluation is three-fold:

![]() We show the utility of

adapting to a (simulated) volatile environment by comparing

against Web processes that do not adapt and use a fixed policy

during execution;

We show the utility of

adapting to a (simulated) volatile environment by comparing

against Web processes that do not adapt and use a fixed policy

during execution; ![]() By being

intelligent in selecting which service provider to query, we show

that adaption using VOC

By being

intelligent in selecting which service provider to query, we show

that adaption using VOC

![]() results in Web

processes that incur less average costs as compared to an

approach that randomly selects a service provider to query at

randomly selected states of the process; and

results in Web

processes that incur less average costs as compared to an

approach that randomly selects a service provider to query at

randomly selected states of the process; and ![]() the average execution time of the Web process

adapted using VOC

the average execution time of the Web process

adapted using VOC

![]() is less than when

the process is adapated using VOC

is less than when

the process is adapated using VOC![]() [5], and varies

intuitively as the expiration times vary.

[5], and varies

intuitively as the expiration times vary.

![\framebox[3.3in]{ \begin{minipage}{3.3in} \begin{tabbing} $<$wsag:Agreement Name... ... \= $<$/wsag:Terms$>$\ \ $</$wsag:Agreement$>$\ \end{tabbing} \end{minipage}}](VOC_Exp-img96.png) |

|

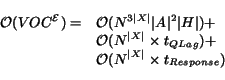

We utilized the MS XBox supply chain and the clinical patient

transfer scenarios (Section 4) for our evaluations. For the

supply chain example, we queried the suppliers for their current

percentage of order satisfaction while in the patient transfer

pathway, we queried the secondary caregivers for their current

vacancy rates.3 In addition to the revised

information about their services, the providers also guarantee a

duration over which the WS parameter values will remain fixed.

4 These distributions may be provided

by the service providers using service-level agreements drawn up

using, say, the WS-Agreement specification [1]. Figure 9 shows a part of the agreement

between MS and the preferred GPU supplier in the XBox scenario.

![]() is defined within the

is defined within the

![]() subtag of

the

subtag of

the ![]() tag. Here, the

entire agreement will expire on January 27, 2007. Further in the

document, the

tag. Here, the

entire agreement will expire on January 27, 2007. Further in the

document, the

![]() subtag of the

subtag of the ![]() tag

defines the provider's rate of GPU order satisfaction

(probability of 0.4). Thus, MS and the contracted GPU manager

have agreed that any order of GPUs from MS will be satisfied 40

percent of the time until the agreement is voided on January 27,

2007.

tag

defines the provider's rate of GPU order satisfaction

(probability of 0.4). Thus, MS and the contracted GPU manager

have agreed that any order of GPUs from MS will be satisfied 40

percent of the time until the agreement is voided on January 27,

2007.

For the service providers when their information has expired,

we model the manufacturer and primary caregiver's beliefs over

their possible parameter values, (

![]() )

in Eq. 1) using beta

density functions. Other density functions such as Gaussians or

polynomials may also be used. Fig. 10

)

in Eq. 1) using beta

density functions. Other density functions such as Gaussians or

polynomials may also be used. Fig. 10![]() shows

the beta densities that represent Microsoft's distribution over

the rate of order satisfaction by the GPU contract manufacturer

ie.

shows

the beta densities that represent Microsoft's distribution over

the rate of order satisfaction by the GPU contract manufacturer

ie. ![]() (

(

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() ,

,

![]()

![]() ), and analogously for

the other suppliers (the Spot Market is assumed to always be

available at a rate of 100 percent). Means of the densities

reveal that the preferred suppliers of both the GPUs and consoles

tend to be less reliable in satisfying orders than other

suppliers. Fig. 10

), and analogously for

the other suppliers (the Spot Market is assumed to always be

available at a rate of 100 percent). Means of the densities

reveal that the preferred suppliers of both the GPUs and consoles

tend to be less reliable in satisfying orders than other

suppliers. Fig. 10![]() shows the density plots over the probability of a

vacancy with the preferred and other secondary caregivers. For

those service providers whose revised information has not

expired, the manufacturer and caregiver's beliefs could be seen

as Dirac-delta functions, with the non-zero value fixed at the

probability,

shows the density plots over the probability of a

vacancy with the preferred and other secondary caregivers. For

those service providers whose revised information has not

expired, the manufacturer and caregiver's beliefs could be seen

as Dirac-delta functions, with the non-zero value fixed at the

probability, ![]() , that was

provided at the time of query. Thus, for this case, the

, that was

provided at the time of query. Thus, for this case, the

![]() at any state of the

process. We emphasize that these densities are marginalizations

of the more complex plots that would account for all the factors

that may influence a supplier's ability to satisfy an order, such

as the time that an order is placed and quantity of the

order.

at any state of the

process. We emphasize that these densities are marginalizations

of the more complex plots that would account for all the factors

that may influence a supplier's ability to satisfy an order, such

as the time that an order is placed and quantity of the

order.

|

MS XBox Supply Chain

Patient Transfer Clinical Pathway

|

In order to perform the evaluations, we simulated a

volatile business environment for each of the two problem

domains. For the supply chain, the rates of order satisfaction

for the preferred and other suppliers were assumed to vary

according to the density plots in Fig. 10. The expiration times were upper

bound to a large time interval and randomly selected within the

bound. The rates of order satisfaction remained fixed until the

corresponding expiration times elapsed, after which, on query,

new expiration times were randomly selected. Other parameters of

the environment such as the WS invocation costs, ![]() , and

, and

![]() , are as given in the

Table 1. The environment

for the patient transfer problem was simulated analogously (see

Table 2).

, are as given in the

Table 1. The environment

for the patient transfer problem was simulated analogously (see

Table 2).

|

In Figs. 11![]() and

and ![]() , we compare

three strategies of adaptation with respect to the average cost

incurred from the execution of the Web process, as the cost of

querying the service providers is increased. These strategies

include no adaptation and keeping the policy fixed, randomly

selecting a single service provider at randomly selected states

of the process, and adapting the Web process using VOC

, we compare

three strategies of adaptation with respect to the average cost

incurred from the execution of the Web process, as the cost of

querying the service providers is increased. These strategies

include no adaptation and keeping the policy fixed, randomly

selecting a single service provider at randomly selected states

of the process, and adapting the Web process using VOC

![]() . Our methodology

consisted of running 100 independent instances of each process

within the simulated volatile environment and plotting the

average cost of executing the process for different query costs.

We ensured that the processes using each of the three strategies

received similar responses from the service providers, and the

expiration times were kept fixed.

. Our methodology

consisted of running 100 independent instances of each process

within the simulated volatile environment and plotting the

average cost of executing the process for different query costs.

We ensured that the processes using each of the three strategies

received similar responses from the service providers, and the

expiration times were kept fixed.

We note that these results are analogous to those reported in

[5] for

VOC![]() and they show that the Web

process incurs lower average costs when adapted using VOC

and they show that the Web

process incurs lower average costs when adapted using VOC

![]() , thereby

establishing the utility of sophisticated adaptation in volatile

environments. In particular, as we increase the cost of querying,

our VOC

, thereby

establishing the utility of sophisticated adaptation in volatile

environments. In particular, as we increase the cost of querying,

our VOC

![]() based approach

performs less queries and adapts the Web process less. For large

query costs, its performance approaches that of a Web process

with no adaptation because costly queries for revised information

are not worth the possible change in the cost of the process due

to adaptation. For smaller query costs, a VOC based approach will

query frequently, though not as much as a strategy that always

queries a random provider.

based approach

performs less queries and adapts the Web process less. For large

query costs, its performance approaches that of a Web process

with no adaptation because costly queries for revised information

are not worth the possible change in the cost of the process due

to adaptation. For smaller query costs, a VOC based approach will

query frequently, though not as much as a strategy that always

queries a random provider.

In Figs. 11![]() and

and ![]() , we compare the

runtimes taken in generating and executing the Web process. We

compare the execution time of a process without any adaptation

(see [4] for the

algorithm), with the execution time of a process adapted using

VOC

, we compare the

runtimes taken in generating and executing the Web process. We

compare the execution time of a process without any adaptation

(see [4] for the

algorithm), with the execution time of a process adapted using

VOC![]() [5], and the execution time

of a process adapted using VOC

[5], and the execution time

of a process adapted using VOC

![]() (Fig. 4). As we increase the

expiration times associated with the revised information obtained

from the providers, the process execution time when adapted using

VOC

(Fig. 4). As we increase the

expiration times associated with the revised information obtained

from the providers, the process execution time when adapted using

VOC

![]() decreases.

Notice that it is upper bounded by the execution times of a

process adapted using VOC

decreases.

Notice that it is upper bounded by the execution times of a

process adapted using VOC![]() and

lower bounded by the runtimes of a process with no adaptation.

This is intuitive because VOC

and

lower bounded by the runtimes of a process with no adaptation.

This is intuitive because VOC![]() always

involves considering all participating WSs for querying,

while no such computations are carried out in a process that does

not adapt. Both these execution times are invariant with respect

to the expiration times. Our results demonstrate the inverse

relationship between expiration times and computational effort

expended on adaptation.

always

involves considering all participating WSs for querying,

while no such computations are carried out in a process that does

not adapt. Both these execution times are invariant with respect

to the expiration times. Our results demonstrate the inverse

relationship between expiration times and computational effort

expended on adaptation.

Our experiments provide two conclusions: First, by augmenting

Web process composition with VOC based calculations, significant

information changes in volatile environments are considered and

used to make better decisions about which services to invoke

next. The comparison of VOC

![]() and static policy

implementations illustrate that the overall average cost of the

Web process when adapted is significantly less than utilizing a

non-changing policy. Second, we demonstrated that if service

providers are able to provide longer guarantees on their service

reliability, less computational effort needs to be spent on

adapting the Web processes. This substantiates the intuition that

in less volatile environments as formalized by higher expiration

times, less adaptation is required to keep the Web process

optimal.

and static policy

implementations illustrate that the overall average cost of the

Web process when adapted is significantly less than utilizing a

non-changing policy. Second, we demonstrated that if service

providers are able to provide longer guarantees on their service

reliability, less computational effort needs to be spent on

adapting the Web processes. This substantiates the intuition that

in less volatile environments as formalized by higher expiration

times, less adaptation is required to keep the Web process

optimal.

Business environments seldom remain unchanged over the lifetime of a Web process. While the environment may change in several ways, we considered changes in the quality-of-service parameters such as rates of order satisfaction in this paper. Prevalent approaches to WS composition utilize a pre-specified model of the process environment to formulate the Web process. However, in a dynamic process environment the model may change over time. We presented a method that intelligently adapts a Web process to changes in parameters of service providers, thereby incurring less costs. While this approach is cost-effective, it may get computationally intensive. Improving on previous work, we showed how service parameter guarantees in the form of expiration times may be used to reduce the computational burden of adaptation. Using two disparate problem domains, we empirically demonstrated the speedups obtained in executing and adapting a Web process to changes in service parameters when using a method that is cognizant of expiration times in comparison to an adaptation strategy that ignores them.

Our future work involves investigating ways in which the volatility of a process environment may be measured and formalised. A formal model of the volatility of a process environment will enable the development of more efficient approaches for adaptation.

[1] A. Andrieux, K. Czajkowski, A. Dan, K. Keahey, H. Ludwig,

T. Nakata, J. Pruyne, J. Rofrano, S. Tuecke, and M. Xu.

WS-Agreement Specification, 2005.

[2] T.-C. Au, U. Kuter, and D. S. Nau.

Web service composition with volatile information.

In International Semantic Web Conference, pages 52-66,

2005.

[3]G. Chafle, K. Dasgupta, A. Kumar, S. Mittal, and B.

Srivastava.

Adaptation in web service composition and execution.

In International Conference on Web Services (ICWS),

Industry Track, 2006.

[4]P. Doshi, R. Goodwin, R. Akkiraju, and K. Verma.

Dynamic workflow composition using markov decision

processes.

Journal of Web Services Research (JWSR), 2(1):1-17,

2005.

[5]J. Harney and P. Doshi.

Adaptive web processes using value of changed

information.

In International Conference on Service-Oriented Computing

(ICSOC), pages 179-190, 2006.

[6] IBM.

Business Process Execution Language for Web Services

version 1.1, 2005.

[7] Enabling an adaptable, aligned, and agile supply chain with

biztalk server and rosettanet accelerator.

Technical Report http:// www.microsoft.com / technet /

itshowcase /content / scmbiztalktcs.mspx, 2005.

[8] R. Muller, U. Greiner, and E. Rahm.

Agentwork: a workflow system supporting rule-based workflow

adaptation.

Journal of Data and Knowledge Engineering.,

51(2):223-256, 2004.

[9] M. L. Puterman.

Markov Decision Processes.

John Wiley & Sons, NY, 1994.

[10] M. Reichert and P. Dadam.

Adeptflex-supporting dynamic changes of workflows without

losing control.

Journal of Intelligent Information Systems,

10(2):93-17, 1998.

[11] K. Verma, P. Doshi, K. Gomadam, J. Miller, and A.

Sheth.

Optimal adaptation in web processes with coordination

constraints.

In International Conference on Web Services (ICWS),

2006.

[12] Web Services Description Language (WSDL) 1.1, 2001.

[13] D. Wu, B. Parsia, E. Sirin, J. Hendler, and D. Nau.

Automating daml-s web services composition using shop2.

In International Semantic Web Conference, 2003.